4/11 – 18/12 2021

Marianne Boesky Gallery | New York

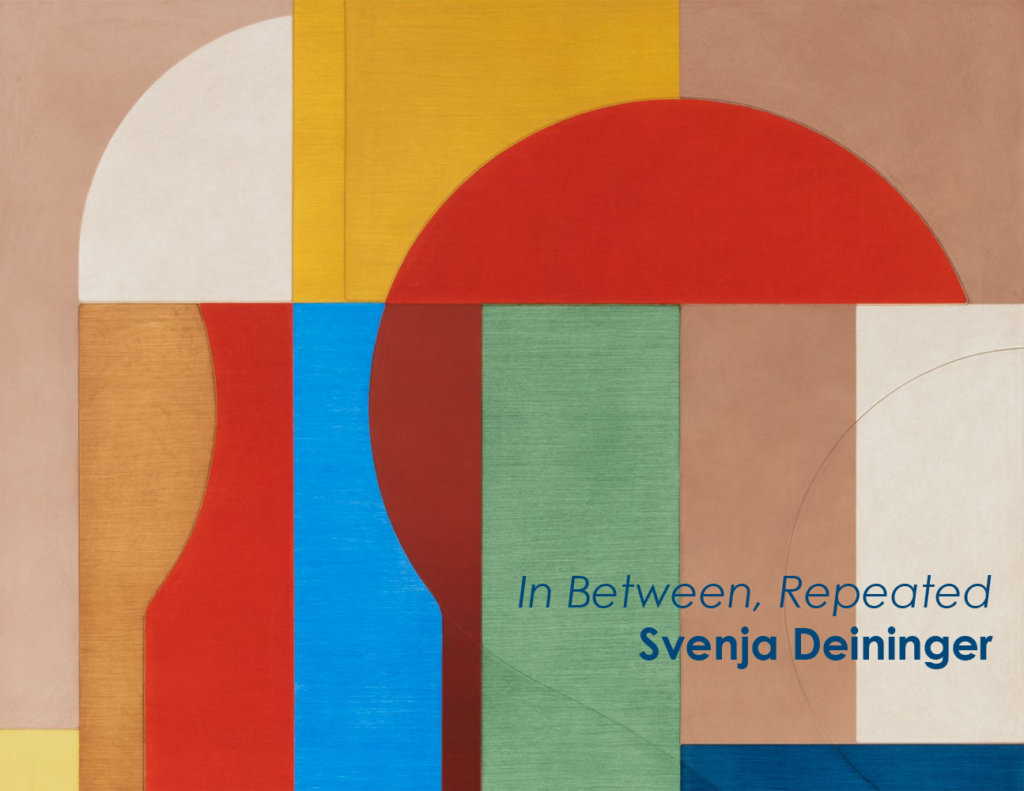

Marianne Boesky Gallery presents Svenja Deininger’s fourth solo exhibition at the gallery. In Between, Repeated features a new body of paintings by Deininger, reflecting the artist’s deliberate yet fluid explorations of the dialogues between shape, color, texture, and surface that reside in her complex compositions.

Svenja Deininger (B. Vienna, 1974) has had solo exhibitions in New York City and throughout Europe, including at the Secession, Vienna; the Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL; and the Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE. She has also had solo exhibitions internationally, including Galerie Martin Janda, Vienna; Federica Schiavo Gallery, Rome and Milan; Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, Italy; Kunsthalle Krems/Factory, Krems, Austria and Kunstforum Wien, Vienna. Deininger has participated in group exhibitions at Museum Haus Konstruktiv, Zurich; Belvedere 21,Vienna; Fundación Banco Santander, Madrid, Spain; Neues Museum Nürnberg, Germany; Victoria Miro Gallery, London; Josh Lilley Gallery, London; the Wiels Center for Contemporary Art, Brussels; Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna and the University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, to name a few. Svenja Deininger lives and works in Berlin, Milan and Vienna.

Luca Cerizza: “Svenja Deininger: reflection as action”

“Do you take more time to paint these canvases or to look at them?”, I asked. This was the first time I met Svenja Deininger at her studio in Milan, in the company of her paintings that were almost ready to be shipped to New York. The artist’s reply confirmed the importance of using a diluted amount of time in at least two aspects of her work: the production of the paintings and their display in the exhibition space. Aspects that involve–I would like to think in equal proportions–a time for looking and a time for doing.

Extended time is crucial in the composition of Deininger’s work: beginning with an initial visual concept, through a gradual process of juxtaposing patterns, tones, shapes, and memories from a vast archive of art historical references, Deininger’s configurations finally emerge. Yet, such a composition can be re-calibrated through a series of changes in the organization of pictorial space and its shades of colour. It is a patient, continuous, even obsessive process of crafting and adjusting the possibilities of a distinct vocabulary of forms and its multiple incarnations.

While a work slowly emerges as a final result of playing with different tensions, including the one between abstraction and figuration, an extended use of time is key to another crucial aspect of Deininger’s works: the surface, if not to say the skin. Upon closer inspection, Deininger’s paintings reveal a carefully measured system of superficial treatments of shapes: a series of patient gestures of painting, scraping, polishing, and repainting. It is a process which allows for light to have a decisive role on each painted surface. The result is a layering of clearly defined patterns treated with a variety of techniques, producing different textures with minute discrepancies in thickness.

These aspects are evident in even the smallest works in the exhibition at Marianne Boesky Gallery. Consider the work installed next to a blue and white stripe painting (Deininger never gives titles to her works). It is surprising to learn that this complex composition actually originated from an initial, although rather schematic, drawing that depicts the bottom and torso of a human figure in simple curves and lines (to what degree, for the artist, is abstraction a way to stave off the presence, or the intrusion, of the human body?). Over a period of about two years, the initial reference has been slowly yet severely altered, resulting in a juxtaposition of different textural treatments and chromatic variations where the initial motif seems unrecognizable.

Taking a few steps back from this close confrontation to view the works from afar, one discovers a series of conversations among Deininger’s paintings that encourage us to read the exhibition as “a scenography orchestrated by the artist” (Martin Herbert). This attitude is born of the artist’s attention to, if not respect for, the position of the public: a consideration for each viewer’s movements and gazes in the space, and for the dialogues that could eventually be established between the works. The artist comprehends that the exhibition is a complex intersection of elements where time plays, once again, a decisive role. The time that creates multiple encounters and connections, an intricate web of memories, that affect the perception of the viewer. The final presentation is, therefore, not only the result of a long process of selection, calibration and eventually friction among the works in relation to the space–a process where looking is reflecting is acting–but also an integral part of her creative practice.

If Deininger aims to construct a dialogue between the works as words in a sentence, where “the goal is a sort of visual writing” (Luigi Fassi), it is more surprising to note that this form of language originates in the cradle of her studio. Even from the exhibition’s incubation phase, the artist carefully crafts the vocabulary to be used in the final phrase/text. Before the exhibition is able to “speak” in the world of the spatial context, that is to say, in the realm of the exhibition space, Deininger has already performed a “collective creation”–a holistic procedure in which different canvases or words are carefully nourished at the same time. As if they were part of a large family, the artist nurtures the singular character of each individual work so that it may thrive in the outside world, even without the support of its companions.

This new display at Marianne Boesky Gallery is no exception: it is the result of ten months of preparation in her Milan studio and of a careful consideration for each work as part of a larger outcome. What could be seen as a novelty is, instead, the role played here by the vertical stripe paintings. Created as part of an almost meditative exercise during a time of seclusion at the onset of the pandemic, these works are compositionally more simplified but not in textural treatment. We are, in fact, tempted to read them as catalogues of different painting techniques. If these works play–not without a touch of irony–with a long tradition of modernist and post-modernist art, in the context of the exhibition they assume an architectural role, resembling the rhythmic and static function of columns. They punctuate the space in alternation with other works differing in size and compositional structure. They are the pillars upon which some smaller paintings can rely, the bars within which the rhythm of the exhibition is structured.

A delicate balancing act between various methodologies, originally related to different art historical developments, Deininger’s practice occupies a peculiar “space in-between”, alien to any particular ideology and driven only by a restless interrogation of the unique possibilities of painterly language. A space where each work is neither self-contained nor autonomous, in the modernist sense of these words, but equally not specifically related to their site. If anything, Deininger’s works are intended to establish dialogues with even the minor characteristics of the exhibition space, as though searching for the most apt vocabulary to launch a conversation.

If Deininger’s work is the result of a careful, processual production mode, such character should not to be interpreted as it has been by minimalist and conceptual artists in the past: as a repetitive or sequential procedure. On the contrary, her practice is an organic, holistic cycle of creation, utilizing the time to look and the time to do as equal, decisive forces. A practice where looking is reflecting is acting.