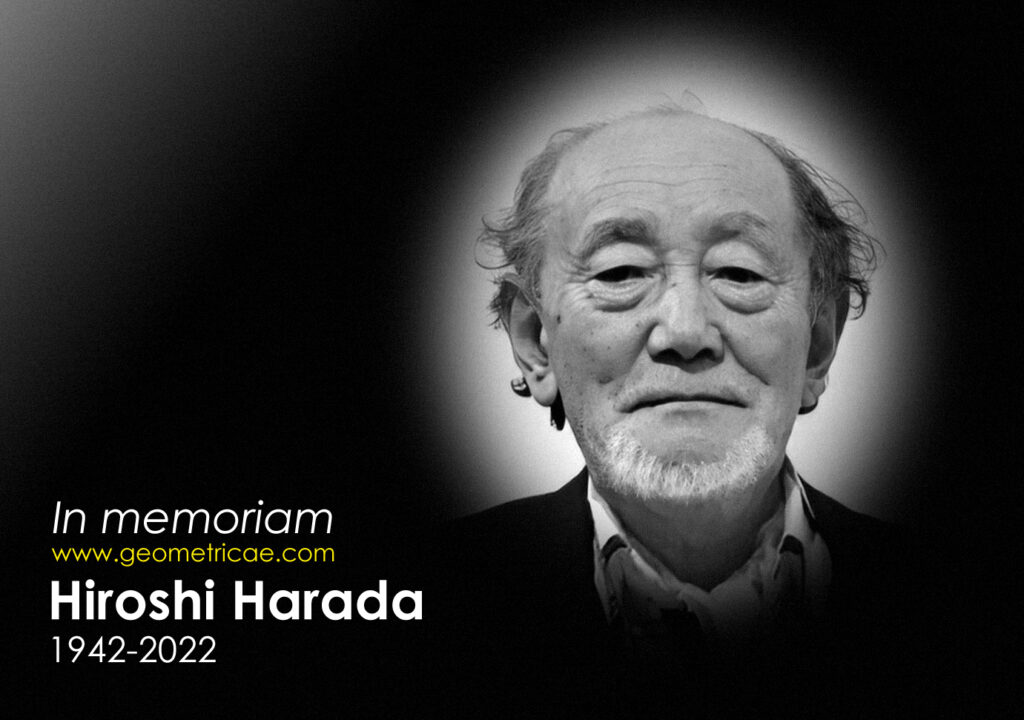

Hiroshi Harada | Saitama Ken | Japan | 1942-2022

Hiroshi Harada | Saitama Ken | Japan | 1942-2022

Harada studied at Musashino School of Art in Tokyo where he met his mentor Takeo Yamaguchi known as one of the leader of the Abstract Japanese Minimalism movement of the mid XXe. Yamaguchi’s works are in the public collections of international museums such as the Guggenheim Museum of New-York. Following the footsteps of his master, Hiroshi Harada was particularly receptive to Western painting and notably to Cézanne’s works whom he considers « the most significant artist ever to exist ». He was also very struck by the work of Paul Klee and Serge Poliakoff. All these influences distanced him from the received ideas of the Academy and even of the Tokyo art world. It was in 1969 that he finally decided to move in Paris.

In Europe, Harada discovered Western abstraction through painters such as Piet Mondrian, Lucio Fontana and Pierre Soulages, but also Malevich, whose compositions have inspired Hiroshi Harada. Unlike Mondrian and other abstract painters, Hiroshi Harada does not use the golden rule to compose his paintings and this confers more humanity and less austerity to his works.

Hiroshi Harada does not respect the laws of pure geometry. The lines he draws are not often steady. Contrary to Mondrian, he does not use the classic principles of the golden rule. He plays with space and tries to give it not only a meaning but also a sensibility.

He produces something coming from the ancient Masters of Chinese and Japanese painting, which is the thought behind the gesture, which prevails over the gesture itself. He metamorphoses this inheritance.

Hiroshi Harada succeeded in creating a poetic space in and for itself, while at the same time adhering to a set of precise rules.

He takes us in a vast universe of which he wants us to feel the most subtle nuances, with as little means as he can. It is, without any doubt, his most noticeable quality, which reminds us also the visual teachings of the Zen Masters.

In order to fully understand Hiroshi Harada’s paintings, one must know his Orient and his West and imagine a “child” of both worlds, a hybrid creator whom has perpetuated some of the heritage of Japanese traditional art and combined it with the modernism of Western painters of the first half of the XX century.